Over 10 years ago, I started my PhD research, looking at how staff from non-profit organizations involve citizens/ service users in their services (as volunteers, peer mentors, etc.), a process known as co-production. My goal was to identify the opportunities and barriers to co-production, and to understand how these practices can be improved to enhance services and outcomes for communities.

Our understanding of the challenges to engaging in co-production and the ways that professionals can improve their approaches to doing so have improved over time, but some big questions still remain: can these approaches stand the test of time? How well do the co-production practices developed at the beginning of a program endure over time? How can we understand what contributes to the sustainability of these approaches?

These are the questions that I explore in my paper “Expectations versus reality: The sustainability of co-production approaches over time” in Public Management Review. In 2019, I went back to two of the cases I explored in my PhD to see what had happened since my initial fieldwork four years prior: were they still engaging people in co-production, and how had things changed? You can read my full paper at the link above, but I wanted to share the model that I developed to illustrate the factors I see as helping to support co-production practices to continue over the longer term.

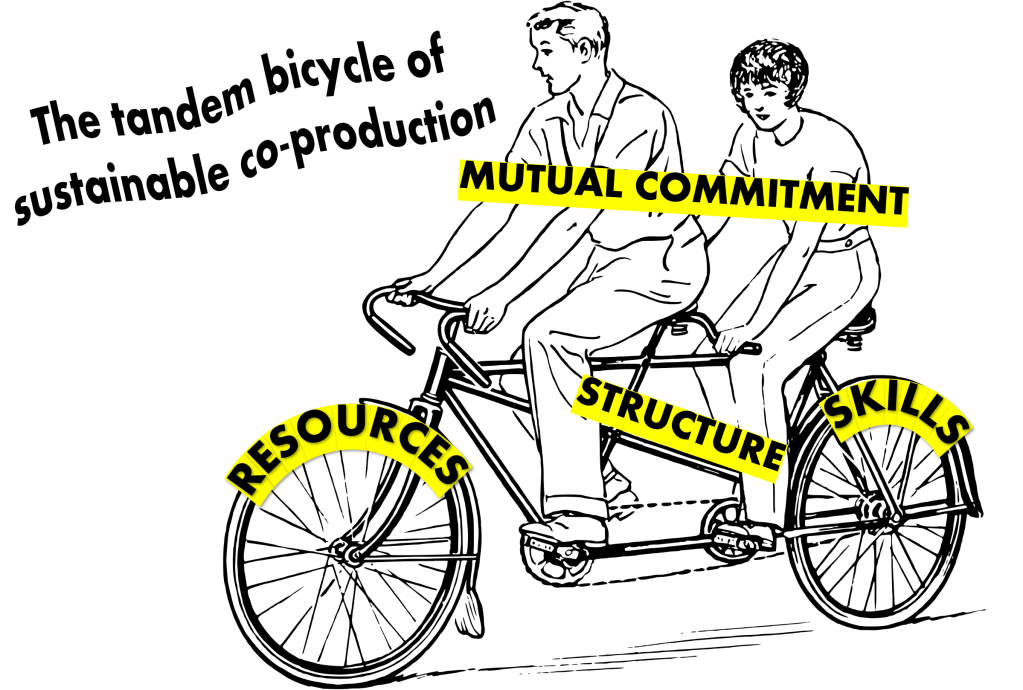

Summarized briefly, co-production is more likely to be sustainable if there is a coherence between structure (program design, the framework for co-production, and organizational processes and systems put in place to enable co-production to take place), resources (both financial and time), skills (capacities and capabilities of citizen and professional co-producers, such as working in groups, facilitation, empathy, and communication), and mutual commitment between citizen and professional co-producers to continue collaborating.

Without sufficient resources and adequate skills of all participants, co-production will likely not be sustainable. This does not mean that long-term co-production requires large grants and highly skilled participants, but that resources must be appropriately and strategically deployed. Co-production frameworks based on informal community engagement generally require people skills but can be undertaken with small budgets, while more structured and large-scale co-production (i.e. formal co-design workshops and large-scale volunteering programs) necessitates a wider range of skills and greater resources. Importantly, however, longer term sources of funding will always provide better support for sustainable co-production than small grants/contracts, which has been one of the biggest barriers, particularly in the UK context. Co-production structures should also be able to adapt if a misalignment between these elements becomes clear – for instance, if it becomes clear that expectations placed on citizens are too high.

These four elements come together into what I call ‘The tandem bicycle of sustainable co-production’. In this model, resources and skills each represent a wheel of the bicycle, while structure represents the bicycle’s frame. Mutual commitment is represented by two riders (citizens and professionals) on the bike. The bike frame (structure) creates the possibility for forward movement, but only if the wheels fit and there is air in the tires (resources and skills). Yet the tandem bike does not move unless both riders are pedalling. Some bike frames are larger than others, in which case they require larger wheels (perhaps even mountain bike tyres), but regardless of the type of bike, the two riders acting together are the only way to get from point A to point B. If the riders are uncomfortable on the bike, they may choose to stop riding. Conversely, if they are particularly enthusiastic, they may be able to ride the bike a long way, even if it is not an excellent bicycle. Riders must also be willing to periodically swap places so that their efforts are shared equally, and for longer rides, it may be necessary to find new riders so that they can continue to pedal.

The tandem bicycle is by no means a perfect analogy, but it is intended to illustrate how sustainability of co-production relies on the interplay between the four elements. This model has concrete applications for public servants and non-profit professionals to make co-production more sustainable – both when initially designing co-production approaches and in evaluating programs.